Land System Change

The transformation of forests, grasslands, and other natural areas through land use and other human actions.

Current State

Forests play a vital role in stabilizing the Earth’s climate, supporting biodiversity, and sustaining human well-being. However, forest loss and other land-system changes continue at alarming rates, driven by complex and region-specific pressures.

Agriculture – especially livestock grazing and cropland expansion – is the leading direct cause, but deeper forces like illegal logging, infrastructure expansion, weak governance, and climate change also play major roles. In the Amazon, for example, deforestation often begins with illegal timber extraction before land is converted to pasture.

The impacts of forest loss are profound. It disrupts biodiversity, increases carbon emissions, alters rainfall patterns, and weakens soil and water systems. It also affects human health, for example by increasing malaria risk in deforested areas. Climate change and water stress are further amplifying damage through heatwaves, fires, and bark beetle outbreaks. If land degradation continues, it will weaken our chances of stabilizing the climate, securing water, and protecting biodiversity. To stay within safe limits, we must urgently protect and restore healthy ecosystems – keeping the land resilient, and Earth livable, for generations to come.

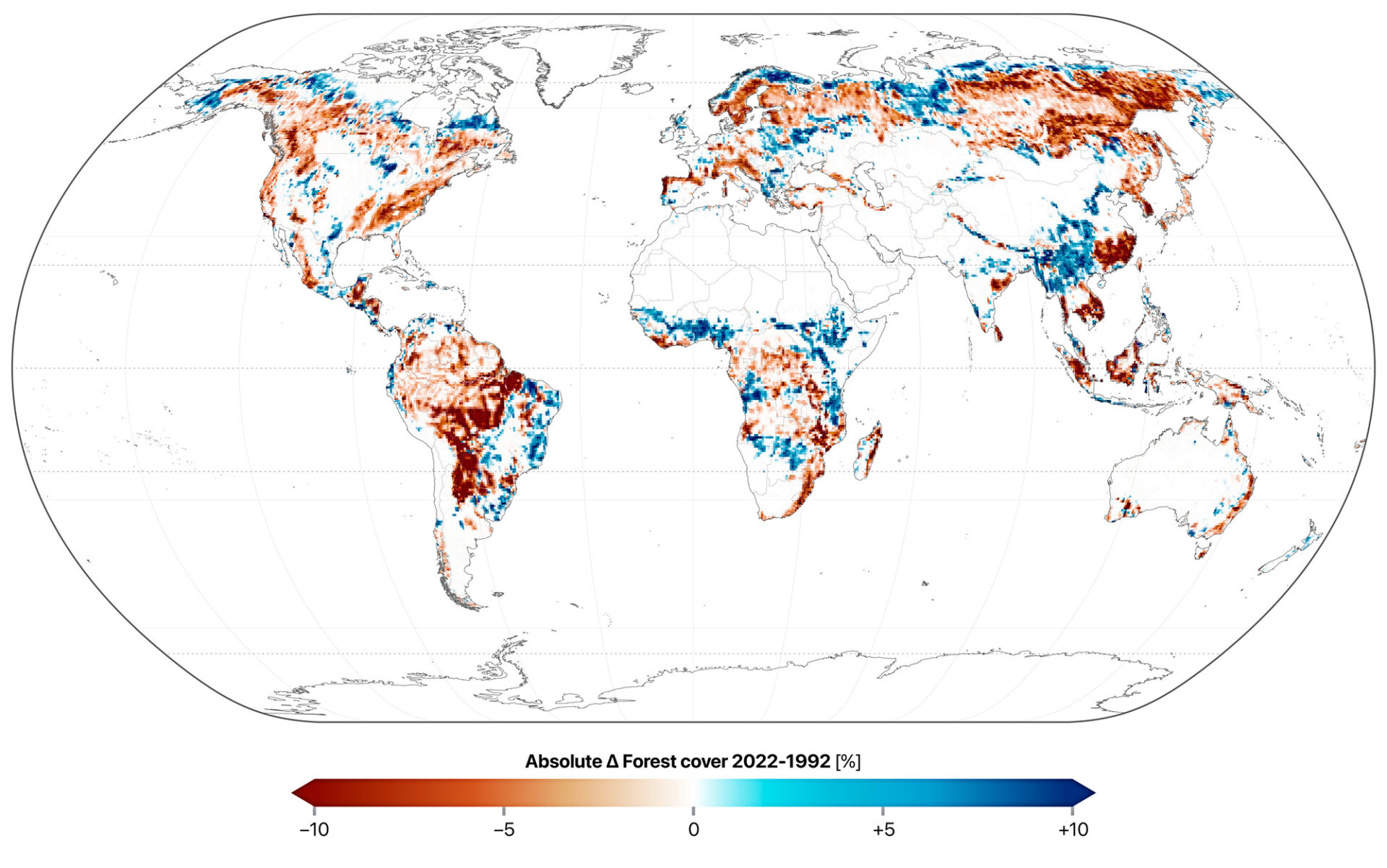

Global map of recent forest cover changes

Colors indicate absolute changes in the percentage of forest cover between 1992 and 2022, with shades of blue representing an increase in forest cover and shades of red a decrease in forest cover (e.g. a change from 60% to 50% forest cover would be indicated by a value of -10%). Areas that had either no forest cover in both 1992 and 2022, or show no change in forest cover, are shown in white. Data from Copernicus (2024).

Patterns of forest loss and gain have been heterogeneous, with prevailing net losses at the biome scale. Continuous pristine forests in the tropics and boreal zones, in particular, have suffered losses of primary forest, while temperate forests, often reflecting managed forestry, have mostly suffered from climate change impacts.

Impacts

Forests and other land ecosystems are the foundation of life on land. They store vast amounts of carbon, keep the climate and water cycles in balance, and provide habitat for countless species. When forests are cleared or degraded, these natural systems lose their ability to regulate the planet’s climate, purify water, and hold soil in place. Because land systems connect so closely with other parts of Earth’s environment—like the atmosphere, water, and living organisms—changes in land use can ripple through the entire Earth system.

Disrupted rainfall and water cycles

Trees release moisture into the air and help guide where rain falls. Losing forests can disturb local and regional rainfall patterns, dry out landscapes, and cause more floods and erosion.

Soil erosion and land degradation

Tree roots hold the soil together and recycle nutrients that plants need to grow. Without this natural protection, soils can wash away, lose fertility, and take decades to recover.

Worsening climate change

Forests act like giant carbon sponges, soaking up and storing carbon dioxide from the air. When they are cut down, that carbon is released back into the atmosphere, adding to global warming and making temperature extremes worse.

Threats to health and livelihoods

Healthy forests support human well-being by providing clean water, food, and stable weather. When they disappear, people can face new risks—from reduced crop yields to higher disease rates and loss of livelihoods.

Farwiza Farhan, Indonesian conservation leader, Founder of HAkA protecting the Leuser Ecosystem, 2024 Ramon Magsaysay Awardee, Planetary Guardian.

“Communities in Borneo and across Southeast Asia are already experiencing the fallout from deforestation: fires, floods, and the erosion of livelihoods. The Three Basins One Lifeline is a call to put people and forests at the centre of our economic decisions because, without healthy forests, there can be no healthy societies.”

Farwiza Farhan, Indonesian conservation leader, Founder of HAkA protecting the Leuser Ecosystem, 2024 Ramon Magsaysay Awardee, Planetary Guardian.

Key Drivers

Agriculture and livestock expansion

Clearing land for crops and grazing is the main cause of deforestation worldwide. Together, farming and ranching account for nearly 90% of recent forest loss. Cropland expansion dominates in Africa and Southeast Asia, while cattle grazing is more common in South America and Oceania. In many cases, forest clearing begins with selective logging before land is converted for agriculture.

Logging and timber production

Forests are widely harvested for wood, paper, and fuel. Logging — both legal and illegal — removes high-value trees and leaves ecosystems fragmented and vulnerable to further clearing. In many regions, the timber and pulp industries remain major sources of forest degradation.

Infrastructure and industrial development

New roads, mines, and urban growth open up previously remote areas, making forests more accessible to agriculture and extraction. These developments often create long-lasting impacts by breaking up habitats and changing how land and water are used.

Climate-driven forest stress

Climate change is increasingly contributing to forest loss. Higher temperatures, droughts, and shifting rainfall patterns weaken trees and make them more prone to fires, pests, and disease. In some regions, these indirect effects are now major drivers of forest decline alongside direct human land use.

Control Variables

The Planetary Boundary for Land-System Change focuses on the balance between natural ecosystems and land converted for human use, especially forests. Forests are vital for storing carbon, regulating water and climate, and supporting biodiversity. The boundary is tracked mainly through the share of original forest cover remaining in different biomes. Large-scale clearing and degradation have pushed many regions beyond safe limits, particularly in the tropics, where forests have been most heavily converted for agriculture, grazing, and resource extraction. Although some areas show signs of recovery through reforestation and regrowth, the overall global trend remains one of continued loss and fragmentation.

Forest Area

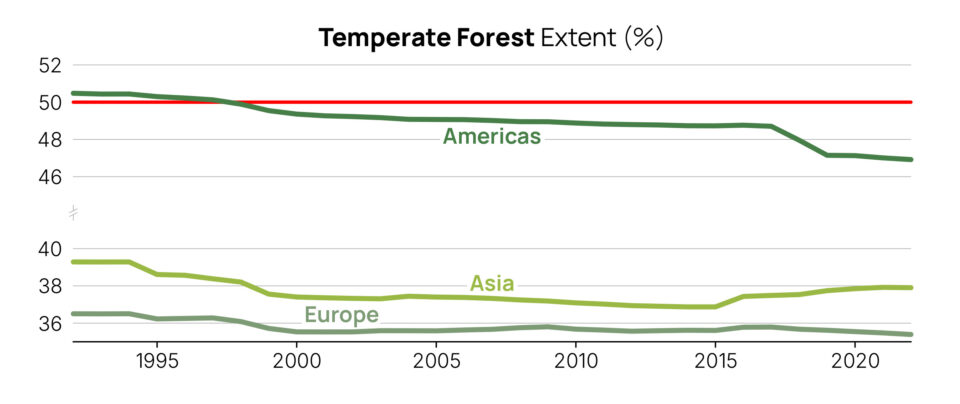

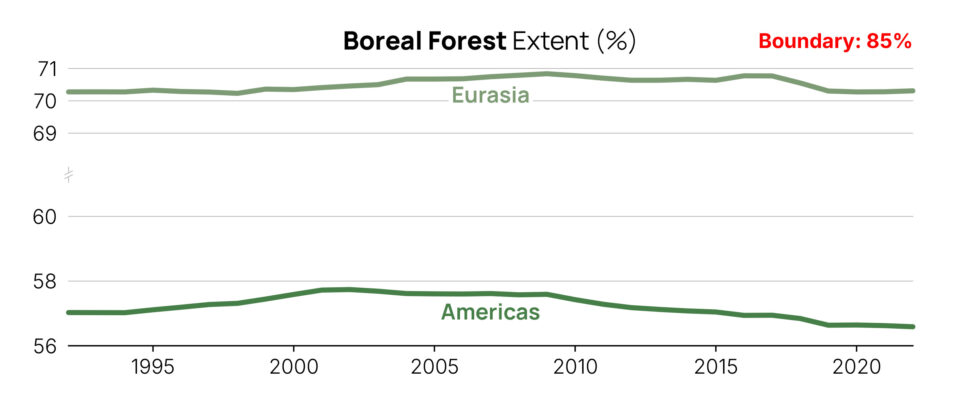

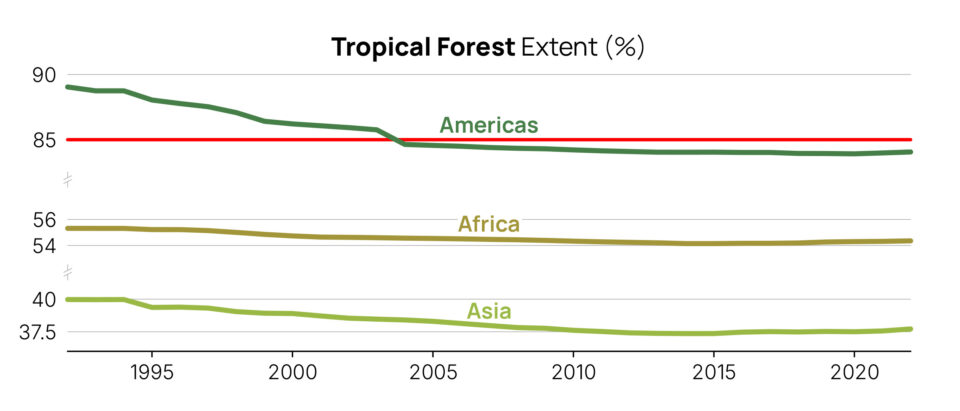

Annual mean forest cover, expressed as a percentage of potential forest cover, globally and for three different biomes (temperate, boreal and tropical) between 1992 and 2022. Red lines show the Planetary Boundaries of 75%, 50%, 85% and 85% for global, temperate, boreal and tropical forests, respectively, while the light green line always represents the baseline of 100% potential forest cover. Data from Copernicus (2024) and Ramankutty & Foley (1999).

As a result of land use and, increasingly, climate change, global and regional forests have been steadily declining over the last few decades across all major forest biomes. Most regions are already significantly below their biome-scale boundaries, while some areas, such as temperate and tropical Americas, have just recently surpassed them.

Definition

Forest area is an accessible quantity and represents the area most responsible for maintaining major global ecological functions. It is expressed as a percentage of the forest cover that would exist in the absence of human land-use changes (‘potential natural forest cover‘). It is determined for boreal, temperate, and tropical forest biomes (as contiguous area per continent) and globally aggregated. Although different land types have distinct functions in the Earth system, forests are most important for the climate system.

Unit

Percentage (%) of potential forest cover.

Historical Range

The value of relative forest cover ranges from 100% (no difference between current and potential forest cover) to 0%.

Planetary Boundary (PB)

The PB for land-system change is set at 75% of the original forest cover, with safe levels specified for different biomes: 85% for boreal and tropical forests, and 50% for temperate forests. These thresholds are based on studies indicating that tropical and boreal forests have a stronger influence on regional and remote climatic conditions than temperate forests.