Modification of Biogeochemical Flows

The disruption of nutrient cycles that regulate soil fertility and the health of water ecosystems, through excessive fertilizer use and pollution.

Current State

In the 20th century, the invention of industrial nitrogen fixation made it possible to convert molecular nitrogen from the atmosphere into reactive forms, such as those used in inorganic fertilisers. Combined with the mining of phosphate rock, this led to a drastic increase in fertilizer application on agricultural land. Because only a part of the fertilizer is actually taken up by crops, large quantities of both nutrients remain in the environment.

Nitrogen is released into the air and stored in groundwater and surface waters. Phosphorus accumulates in soils and is released into surface waters via soil erosion and surface runoff. Excess nutrients can have negative effects on biodiversity and the resilience of ecosystems on land, in freshwater and in the ocean, which are adapted to specific nutrient levels. Currently, losses of both nutrients to the environment are disrupting ecosystems beyond the safe level.

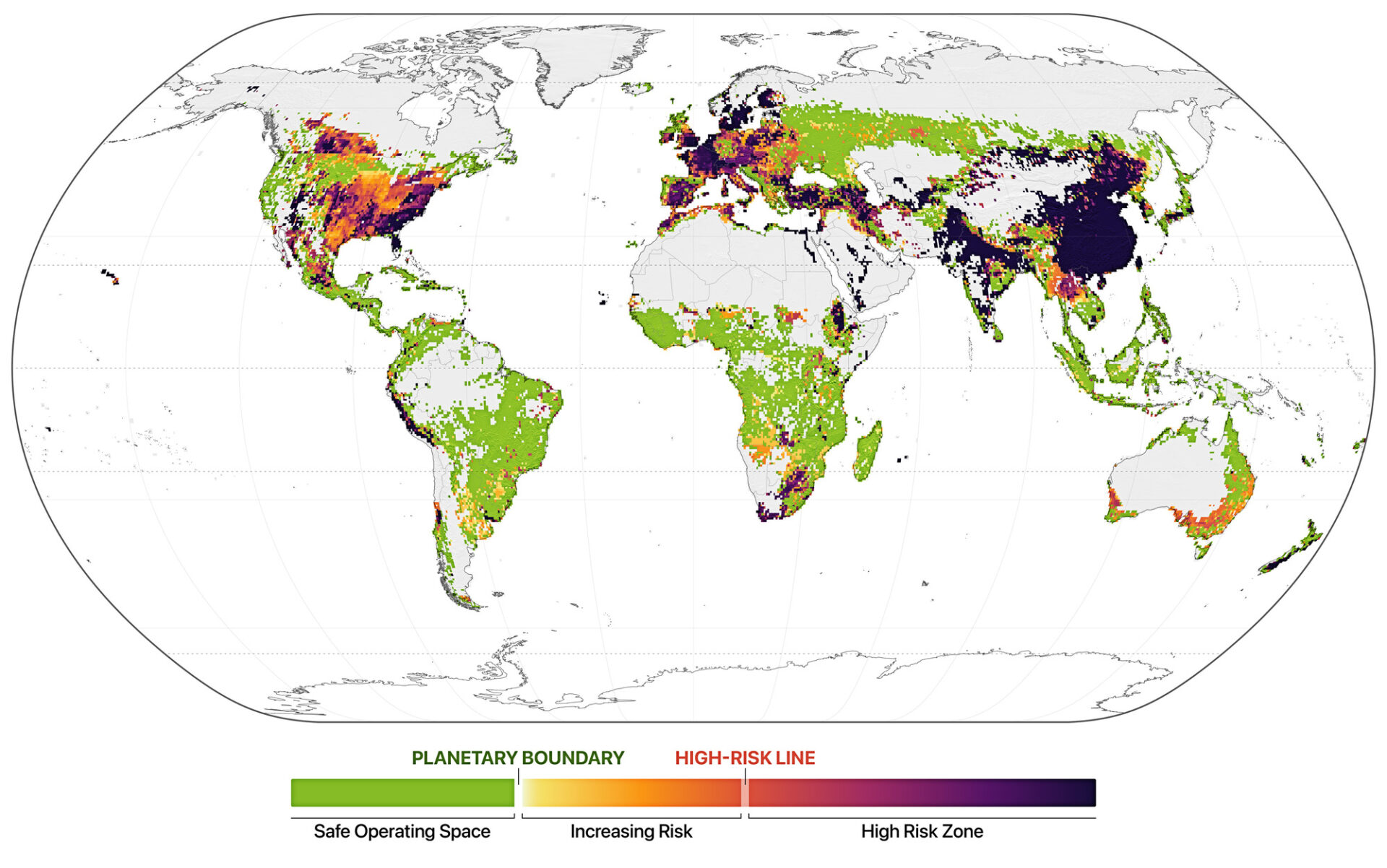

Global risk map of the disrupted nitrogen cycle

Nitrogen use in agriculture has exceeded safe ecological limits in several regions of the world, particularly in parts of Asia and Europe, indicating significant environmental risks.

The regional boundary status is calculated based on agricultural nitrogen surplus in the year 2020 and estimates of regional surplus boundaries. Values range from within the Safe Operating Space (green; no exceedance of regional surplus boundaries) to the Zone of Increasing Risk (orange), and extend to the High-risk zone (red/purple). Based on data from model runs with IMAGE-GNM, using the methodology of Schulte-Uebbing et al. (2022).

Impacts

Exceeding safe limits for nitrogen and phosphorus has wide-reaching consequences for ecosystems, climate, and human well-being. Once released into the environment, these nutrients move through water, air, and soil, creating knock-on effects across multiple Earth system processes. They pollute waterways, alter species composition, and even contribute to global warming and ozone depletion. Because nutrient cycles are so tightly connected to other boundaries — including Climate Change, Biosphere Integrity, and Land-System Change — transgressing them has cascading effects across the Earth system.

Nutrient overload in water systems

Excess nitrogen and phosphorus run off farmland into rivers, lakes, and coastal waters. This leads to algal blooms that deplete oxygen, creating “dead zones” where fish and other aquatic life cannot survive.

Ecosystem imbalance and biodiversity loss

High nutrient levels favor fast-growing plants and algae, crowding out other species and reducing biodiversity in both water and on land. Changes in the nitrogen-to-phosphorus ratio can further destabilize entire ecosystems.

Air pollution and climate impacts

Reactive nitrogen contributes to smog, fine particles, and greenhouse gases like nitrous oxide (N₂O), which warms the planet and harms the ozone layer. These gases link nutrient pollution directly to both climate change and air quality.

Economic and social impacts

Nutrient pollution damages agriculture, fisheries, and tourism, while cleanup efforts are costly. Communities dependent on freshwater or coastal resources face economic losses and health risks from contaminated water supplies.

Ralph Chami, Financial economist, Co-founder of Blue Green Future and Rebalance Earth, pioneer of “Science-Based Finance”, Planetary Guardian.

“We need a new approach to valuing nature, one that is grounded in science-based economics. I love the Planetary Boundaries science as it can serve as a practical measurement framework to let us know how we are doing and what we need to fix.”

Ralph Chami, Financial economist, Co-founder of Blue Green Future and Rebalance Earth, pioneer of “Science-Based Finance”, Planetary Guardian.

Key Drivers

Fertilizer use and intensive agriculture

The widespread use of synthetic fertilizers and nitrogen-fixing crops has transformed global food production, helping to feed a rapidly growing population. But much of the nitrogen and phosphorus applied to fields is not taken up by crops, instead leaching into water and air. This surplus disrupts natural nutrient cycles and drives boundary transgression.

Fossil fuel combustion and industrial emissions

Burning fossil fuels releases nitrogen oxides (NOx) into the atmosphere, adding to reactive nitrogen levels far beyond agricultural sources. These compounds contribute to smog, acid rain, and the long-distance transport of nitrogen pollution.

Low nutrient efficiency and poor recycling

Modern agriculture loses a large share of nutrients through runoff, erosion, and food waste. Limited recycling of livestock manure and human waste, combined with inadequate wastewater treatment, allows valuable nutrients to escape rather than re-enter production cycles.

Uneven and historical nutrient use

While nitrogen and phosphorus use has stabilized in Europe and North America, these regions still carry the legacy of decades of heavy fertilizer application, which continues to affect soils, groundwater, and coastal waters. Meanwhile, nutrient use is rising sharply in Asia due to population and economic growth, while parts of Africa and Oceania remain nutrient-limited, showing that imbalances exist in both historical and current contexts.

Control Variables

The Planetary Boundary for Biogeochemical Flows tracks the global cycles of nitrogen and phosphorus — two essential nutrients for life. The nitrogen boundary measures how much reactive nitrogen humans introduce each year, mainly through fertilizers and fossil fuel combustion. The phosphorus boundary has both global and regional dimensions; the regional one focuses on how much phosphorus flows from land into freshwater systems, while the global one concerns the transport of phosphorus into the ocean . Both boundaries have been substantially exceeded.

Phosphorus (P) Flows

Phosphorus inputs to global cropland. This graph shows the estimated global application of mineral phosphorus on all croplands (in Tg P year-1, i.e. million tons per year) from 1961 until 2022. Data from Ludemann et al. (2024).

The significant increase over time in phosphorus application highlights the growing reliance on phosphorus in agriculture over the decades.

Definition

The phosphorus boundary consists of a regional component, aiming to prevent eutrophication of freshwater systems, and a global component, aiming to prevent largescale ocean anoxia. The regional boundary uses the application of mined phosphorus to erodible soils as an indicator of phosphorus flow into freshwater systems, while the global boundary is based on riverine transport of phosphorus to the ocean.

Unit

Teragrams of Phosphorus per Year (Tg of P year-1). 1 teragram equals 1 million metric tons.

Historical Range

Before human intervention, phosphorus flows were low (~2.5 Tg P year-1 from land to freshwater and ~1.3 Tg P year-1 of export to the ocean). Human activities have increased flows from land to freshwater systems through a global application of mined phosphorus to cropland of around 18.2 Tg P year-1 (regional, aggregated) and have increased phosphorus flows to the ocean to around 4.4 Tg P year-1 (global), largely due to fertilizer use.

Planetary Boundary (PB)

The regional boundary is set to an application of 6.2 Tg P per year, while the global boundary is established at a flow of 11 Tg P per year, which is roughly ten times the natural flow rate. Here, we focus on the regional boundary, as it is more limiting than the ocean boundary.

Nitrogen (N) Fixation

Nitrogen inputs to agriculture. This graph shows the estimated global anthropogenic nitrogen fixation, through fertilizer application and biological fixation, on all croplands (in Tg N year-1, i.e. million tons per year) from 1961 until 2022. Data from the IMAGEGNM model and FAO.

The steady increase in nitrogen inputs over time is a result of both cropland expansion and higher nitrogen use rates, reflecting the growing demand for agricultural productivity.

Definition

The nitrogen boundary sets a threshold for anthropogenic nitrogen fixation in agriculture. It is the total amount of industrial nitrogen fixation through the Haber-Bosch process for fertilizer production and the intentional biological fixation through leguminous plants that host nitrogen-fixing bacteria in their roots.

Unit

Teragrams of Nitrogen per Year (Tg of N year-1). 1 teragram equals 1 million metric tons.

Historical Range

Human activities have increased anthropogenic nitrogen fixation rates from 0 to approximately 190 Tg of N year-1 globally, mainly through fertilizer use. As a result, human interference in the global nitrogen cycle now exceeds the total flux of fixed nitrogen from all natural sources, both on land and in the ocean.

Planetary Boundary (PB)

The nitrogen PB targets industrial and intentional biological nitrogen fixation, setting a threshold at 62 Tg N year-1. This boundary is established based on empirical data, environmental considerations, and the precautionary principle to uphold biogeochemical balance and safeguard ecosystem health.