Ocean Acidification

Increasing carbon dioxide absorption is making the oceans more acidic, threatening marine ecosystems.

Current State

The ocean absorbs a substantial proportion of the CO₂ released by human activities. This oceanic uptake slows climate change but causes the seawater to become more acidic – a process known as ocean acidification. Ocean acidification has now gone beyond what is considered safe for marine life. A key indicator of ocean acidification is the aragonite saturation state. Aragonite is a form of calcium carbonate that many marine organisms – like corals and shellfish – use to build their shells and skeletons.

As more CO₂ enters the ocean, it forms carbonic acid, which lowers the pH but also reduces the availability of carbonate. This makes it harder for these organisms to grow and survive. Marine ecosystems are already feeling the effects. Cold-water corals, tropical coral reefs, and Arctic marine life are especially at risk as acidification continues to spread and intensify.

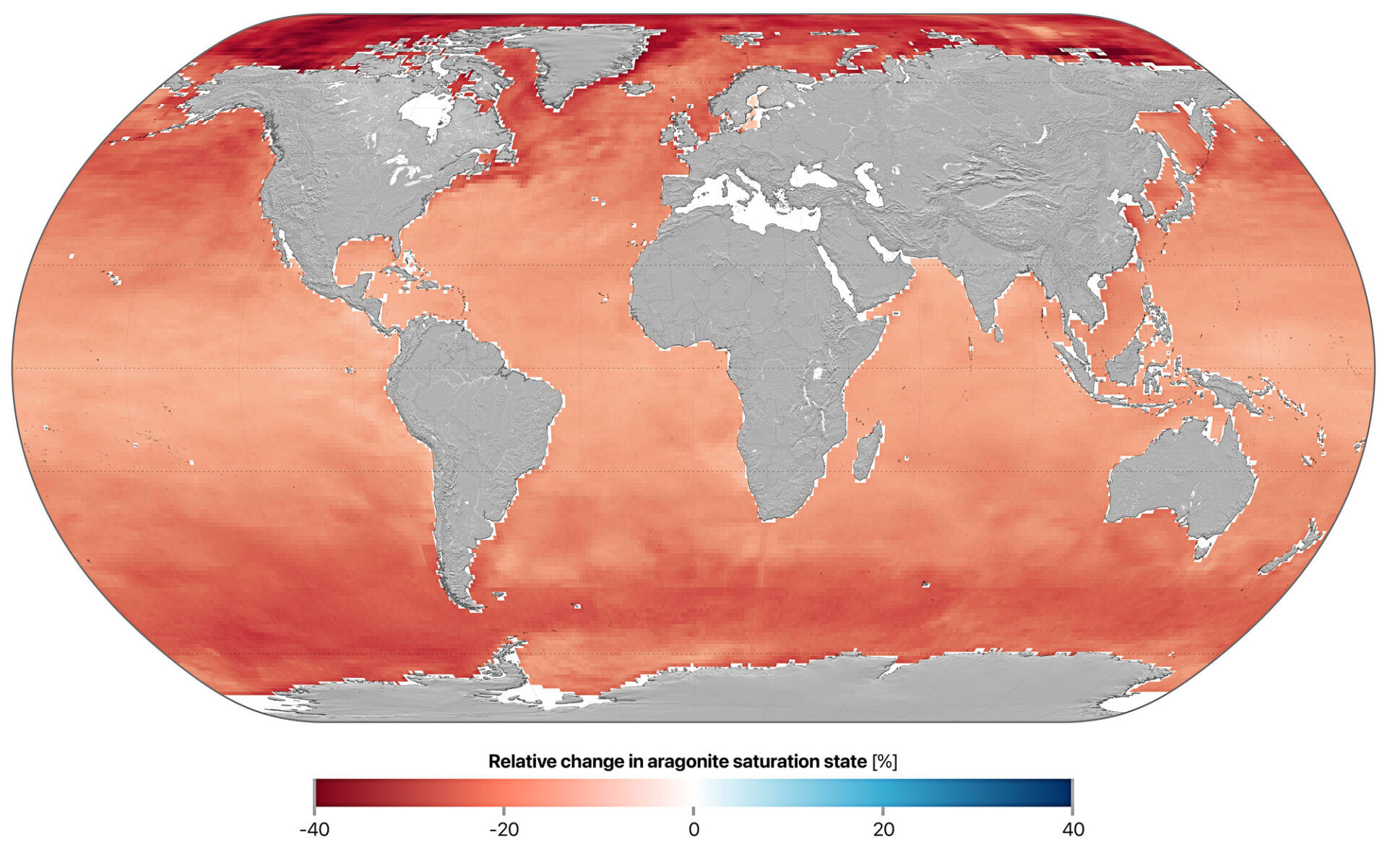

Global map of Ocean Acidification

The Ocean has significantly acidified globally, particularly in the Arctic and Southern Ocean regions. This figure shows how the global surface aragonite saturation state has changed over time. It has declined significantly in recent decades, and has now breached the Planetary Boundary. The baseline (green line) is a revised estimate of the pre-industrial aragonite saturation state around the year 1750. Because it is higher than previous estimates, the revised Planetary Boundary (set at 80% of the pre-industrial state; red line) is also higher – meaning today’s ocean is even further from its pre-industrial state than previously thought. Ocean acidification has gone beyond safe limits, increasingly endangering marine ecosystems.

Impacts

Ocean acidification affects both marine ecosystems and the planet’s ability to regulate climate. As the ocean absorbs more carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, its chemistry changes, reducing the availability of carbonate ions needed by shell-forming organisms. This disrupts marine food webs, weakens coral reefs, and even limits the ocean’s capacity to absorb CO₂, creating feedbacks that intensify climate change.

Marine life under stress

Shell-forming organisms such as corals, mollusks, and tiny sea snails (pteropods) struggle to grow and survive as seawater becomes more acidic. This disrupts entire food webs, as many fish and larger species depend on these organisms for food or habitat. Coral reefs — already stressed by marine heatwaves — face additional challenges, as acidification slows recovery after bleaching and reduces reef resilience.

Deep-sea and regional impacts

In deeper waters, acidification is progressing faster because of lower buffering capacity. The aragonite saturation horizon — the depth where calcium carbonate begins to dissolve — is rising closer to the surface, threatening deep-water corals and other cold-water ecosystems. Regionally, the Arctic is acidifying fastest due to its cold temperatures and freshwater inputs, while tropical and coastal waters face added pressures from nutrient runoff, upwelling, and pollution.

Weakened ocean buffering and CO₂ uptake

Acidification reduces the ocean’s natural capacity to absorb carbon dioxide, slightly slowing one of Earth’s key climate regulation mechanisms. As carbonate ions decline, the ocean’s buffering system weakens, allowing more CO₂ to remain in the atmosphere and reinforcing global warming.

Sylvia Earle, Oceanographer, explorer, author, National Geographic Explorer at Large, President & Chair of Mission Blue, Planetary Guardian.

“The Ocean is our planet’s life-support system. Without healthy seas, there is no healthy planet. For billions of years, the ocean has been Earth’s great stabiliser: generating oxygen, shaping climate, and supporting the diversity of life.”

Sylvia Earle, Oceanographer, explorer, author, National Geographic Explorer at Large, President & Chair of Mission Blue, Planetary Guardian.

Key Drivers

Rising atmospheric CO₂ and climate change

Human-caused carbon dioxide emissions are the dominant driver of ocean acidification. As more CO₂ dissolves in seawater, it forms carbonic acid, which lowers pH and reduces the availability of carbonate ions essential for marine organisms.

Warming oceans and changes in circulation patterns influence how CO₂ is absorbed and mixed through the water column. These processes can accelerate acidification in certain regions, especially in colder or poorly mixed waters.

Local and regional pollution

In coastal areas, nutrient runoff from agriculture and wastewater, along with upwelling and high biological activity, can locally intensify acidification. These pressures add to global CO₂-driven trends, creating strong regional and seasonal variability.

Control Variables

The Planetary Boundary for Ocean Acidification is defined by the aragonite saturation state of surface seawater — a measure of how easily marine organisms can build shells and skeletons from calcium carbonate. The Ocean Acidification boundary was been formally assessed as transgressed in 2025, making it the seventh Planetary Boundary to be outside of its Safe Operating Space and confirming that human CO₂ emissions have pushed ocean chemistry beyond safe levels.

Aragonite Saturation State (Ω)

Definition

Aragonite is a form of calcium carbonate that many marine organisms – such as corals and shellfish – use to build their shells and skeletons. The aragonite saturation state (Ω) reflects the availability of carbonate in seawater relative to the amount needed for stable aragonite formation, with values below 1 indicating corrosive conditions. Ω is closely tied to CO₂ levels in the atmosphere, making it a useful indicator of the impact of rising CO₂ on both ocean chemistry and marine organisms.

Unit

Dimensionless.

Historical Range

Ω varies by region, predominantly ranging from 3.3 to 4.0 in tropical regions to 1 to 2 in polar regions.

Planetary Boundary (PB)

The PB for global mean surface Ω is set at 2.86, which is 80% of the pre-industrial value of 3.57. The 80% threshold was selected with the aim of preventing large-scale aragonite undersaturation in high-latitude waters, while maintaining well-oversaturated conditions in low-latitude regions, thereby limiting harmful impacts on marine calcifiers.